Story & photo by Janie Magruder

His talk was geared to meet the emotional maturity of fourth- and

fifth-graders at Kyrene del Cielo Elementary who sat at his feet with rapt attention. There were no grisly photos of Holocaust victims, nor grim descriptions of their murders.

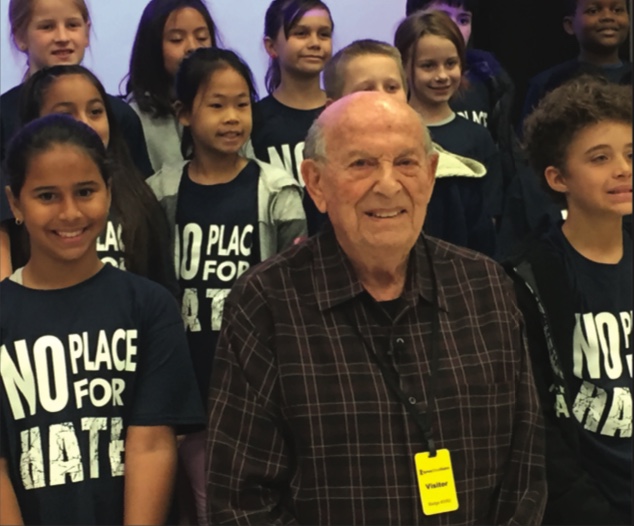

But Oskar Knoblauch’s 90-minute message about respect, goal setting, standing up for yourself and others— smiling all the while—was sobering nonetheless, for the 150 students, staff and parents assembled at the West Chandler school.

“The Holocaust was all around us, no matter where you went,” said Knoblauch, a German-born Jew who, at age 11, fled to Poland in 1936 with his parents and two siblings.

Two years later, the Nazis seized the boy’s new country, upending his life all over again.

“You could have been in your apartment, and you go to work in the morning and come home in the evening, and half your family has disappeared, without cause or reason,” said the 93-year-old old Phoenix resident, author of A Boy’s Story—A Man’s Memory: Surviving the Holocaust, 1933-1945.

“You didn’t have to be in a camp to be in the Holocaust.”

Knoblauch’s appearance was tied to Cielo’s participation in No Place for Hate, a national student-run initiative sponsored by the Anti- Defamation League. To be recognized as a designated partner, schools must host at least three events per year focusing on inclusion and anti-bullying, said Principal Tammy Thaete. Cielo’s club advisers, teachers Hope Massar and Lauren Stewart, helped students invite Knoblauch.

“We need to share his personal story to help ensure the atrocities of the Holocaust never happen again,” Thaete said. “Hearing a firsthand account is extremely meaningful for students, and they tend to think about the message long after the presentation is over.”

Knoblauch’s early childhood was happily filled with school, play time, sports, friends and the love of family. His father Leopold was a World War I veteran who was self-employed, and his mother Ruzia was a homemaker. The couple raised their children to give “110 percent” to everything, to hate no one and be proud of their heritage.

As Adolf Hitler came into power with his poison messages of fear and hatred, Knoblauch was just finishing third grade.

“The rhetoric started,” he said. Referring to the oft-quoted line that a lie told often enough becomes the truth, he noted: “Hitler and the Nazis were expert liars.”

Across Germany, free speech was threatened, books were burned and concentration camps were built, even as Hitler promised to “make Germany great again,” Knoblauch said.

The boy was threatened by bullies many times, but he refused to beg or cower. Rather, he said, he stood tall, asserted his pride and smiled widely.

Eventually, the bullying stopped.

In 1936, the Knoblauchs fled Germany for Poland and, for a time, their life was fairly normal. “Poland was my proving ground,” he said. “I learned a lot, including to speak Polish, and I learned you can achieve anything you set your mind to.”

But when the Nazis occupied Poland, the family was forced into the Krakow Ghetto, where they lived in a tiny apartment without showers, heat or blankets and very little food. They faced hard labor and the constant fear of death.

Knoblauch’s parents pulled their children from school, and for 18 months they stayed in the apartment, except for Leopold, who rode his bicycle to work.

“A 10-year-old boy in a Nazi uniform said to my Dad, ‘Get off that bike, that bike is mine,’” he said. “A 10-year-old boy had more power than a World War I veteran.”

Knoblauch eventually went to work retrieving garbage from the streets of Krakow. He met various “upstanders,” other prisoners and even Nazi soldiers who stood up for the persecuted at great risk to themselves. They gave him bread for his family and kept him out of the Nazi death camps by persuading authorities to give him work.

Not everyone was as fortunate, he noted, showing the Cielo community a photo of rail car in which Jews were transported to the horrific camps. The image brought a flood of emotions to parent Matthew Figueroa, who’s visited the Auschwitz camp in Poland, as well as the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

“Seeing the rail car was tough,” Figueroa said, turning to his fifth-grade daughter Sienna. “In the museum, you can walk through one and see the fingernail marks of people who were scratching to get out.”

Knoblauch’s dramatic memories were peppered with lessons that are as applicable today — to children and adults — as they were 80 years ago.

“Every day is a good morning, even if it’s cloudy or raining,” he said.

“You can breathe, you are alive, and you realize that life is a gift. It was given to you, and you have to cherish it.”

Knoblauch emphasized the importance of words, that they matter, and he urged the students to always tell the truth. He encouraged them stand tall, be proud and keep a positive attitude. He reiterated the value of respect, of being an “upstander,” and of contemplating and setting high goals.

That resonated with Sienna Figueroa, who hopes to become an actor.

“I feel like I want to take my goals and try harder in life,” she said.

A special father-daughter moment happened when Knoblauch reminded the students to do their best because their parents won’t always be around to take care of them.

“Sienna made eye contact with me when he said, ‘I’m not going to be here forever,’’ said Figueroa, tears in his eyes. “I was just telling her that this morning.”