By M.V. Moorhead

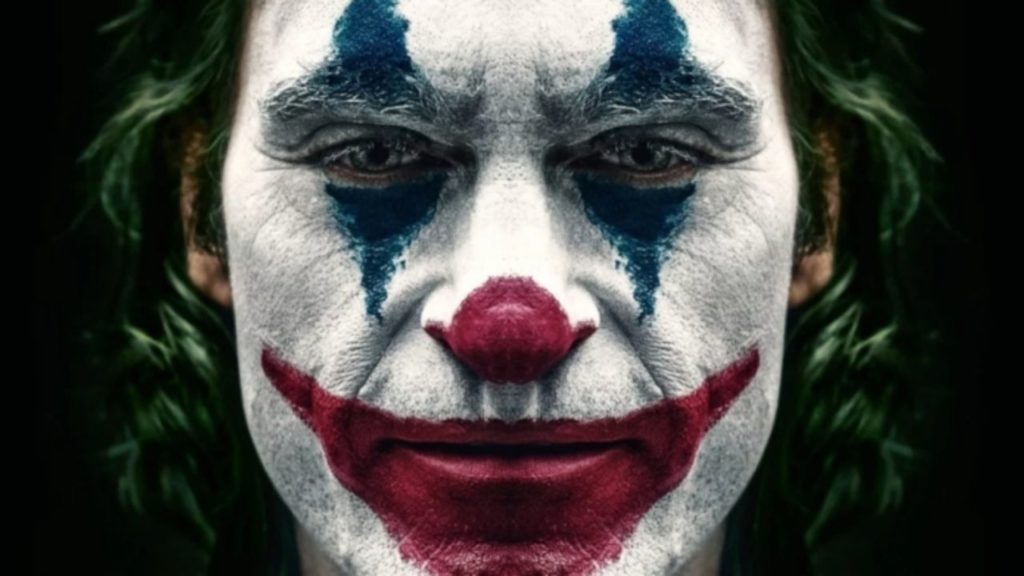

Late Saturday evening this past weekend I was approaching the door of a Quik Trip when I glanced up to notice The Joker headed to the same spot from the other direction. By which I mean not the campy super-villain from Batman comics or the ‘60s-era Batman TV show, but the troubled-loner Joker as played by Joaquin Phoenix in the Todd Phillips movie Joker, now in theaters.

I was momentarily startled; then I remembered it was the weekend before Halloween. I held the door and let the young man enter before me. But there’s no denying that his costume gave me more of a genuine chill than your run- of-the-mill Halloween party hobgoblin.

As a cultural phenomenon, Joker appears not to be in any hurry to go away. Four weeks after its opening, it returned to the No. 1 spot at U.S. box offices, unseating another revisionist take on an iconic villain with Maleficent: Mistress of Evil.

Even before its opening, Joker was the subject of anxious controversy for its perceived appeal to alienated young men. There was concern that it could even lead to violence akin to the horrific 2012 shooting at a movie theater in Aurora, Colo., during a midnight show of The Dark Knight Rises, by a man who reportedly identified with the character. This shooting killed 12 people and wounded dozens of others.

So far, thankfully, actual violence connected to Joker seems largely not to have materialized. But this doesn’t alter the concern of many social critics that the movie could be seen as validating, even glamorizing, the “incel” (“involuntary celibate”) sensibility and other angry, self-pitying and sometimes violent mindsets held by troubled young loners.

For those who haven’t seen it: The title character of Joker is Arthur Fleck, a young man who lives with his mother in a low-rent apartment in a run-down, monochrome, garbage-strike-stricken ‘70s-era version of Gotham City.

Arthur suffers from a condition that makes him laugh uncontrollably and inappropriately. He’s a for-hire clown, work he loves and takes seriously, but which makes him the target of everyone from street thugs to treacherous coworkers.

He can’t even playfully make faces to amuse a child on the bus without getting scolded by the kid’s mother.

In short, he’s a man more sinned against than sinning; a man who might legitimately wonder if fate somehow simply has it in for him. He suffers mightily and through no real fault of his own, and when he turns to violence initially, it’s in response to being abused by despicable strangers on a subway; for the most part he acts in self-defense.

Eventually, as he self-consciously adopts the “Joker” persona, his crimes become more psychotic and calculated, but it isn’t hard to imagine the character’s actions seeming understandable and even justified by isolated, antisocial young men.

When I saw the film, about a week before it opened, what struck me was how powerful Phoenix was in the role, and how curiously unsatisfying the rest of the movie was.

I certainly don’t think that Phillips and the other filmmakers had the slightest intention of justifying violence as a response to feeling lonely and persecuted, but by creating a character who suffers to such an improbably unrelieved degree, and so blamelessly, they’ve made a movie that can be read that way.

It may not be what the film’s makers had in mind, but apart from showcasing a brilliant piece of acting, it’s hard to say just what they did have in mind, so this dark interpretation has naturally filled the vacuum in Joker’s thematic center.

The real, if grim, value of this movie may be to suggest how widespread this feeling of alienation is in our current angry, hectic, chaotic, social-media- driven lifestyle. Joker may be less a drama and more the description of a symptom: We’re hearing a lot of laughter these days, but there doesn’t seem to be a lot of joy behind it.

Joker is rated R due to “strong bloody violence, disturbing behavior, language, and brief sexual images.” It remains in wide release.